Farrell's concert series, "Heaven After Dark," is the sum of the legendary rocker's creative ambitions and experiences in the events space and beyond.

Losing a million dollars will teach a man a few things. Just ask Perry Farrell.

Farrell has maintained just the right combination of DIY vein and an want for controlled unconnectedness to protract effectuating his lifelong ambitions in music—but it hasn't unchangingly been sunshine and roses for the legendary rocker.

Today the Jane's Addiction frontman is planting the seeds of a promising global event series, "Heaven After Dark." While the event itself has the makings of a hit, Farrell needed to wield decades of wits and intangibles to make it so.

Ahead of the upcoming "Heaven After Dark" takeover of Los Angeles' Catch One in early December 2022, Farrell unprotected up with EDM.com for a unslanted interview wherein he shared his view on the state of flit music's past and present, and the underlying momentum powering his would-be concert series.

Speaking with Farrell, it's well-spoken his latest creation—developed slantingly his wife, Etty Lau Farrell—is arguably his most personal live event offering intersecting with electronic music culture. That in itself is a statement which carries considerable weight given it's coming from the progenitor of Perry's Stage at Chicago's Lollapalooza, one of the most iconic live platforms for electronic flit music artists on the worldwide festival circuit.

Farrell is certainly proud of Lollapalooza's increasingly global reach. He proudly points out that the minion brand, which has launched satellite events throughout South America and Europe, is currently executing on its unvigilant ambitions to expand to India in 2023.

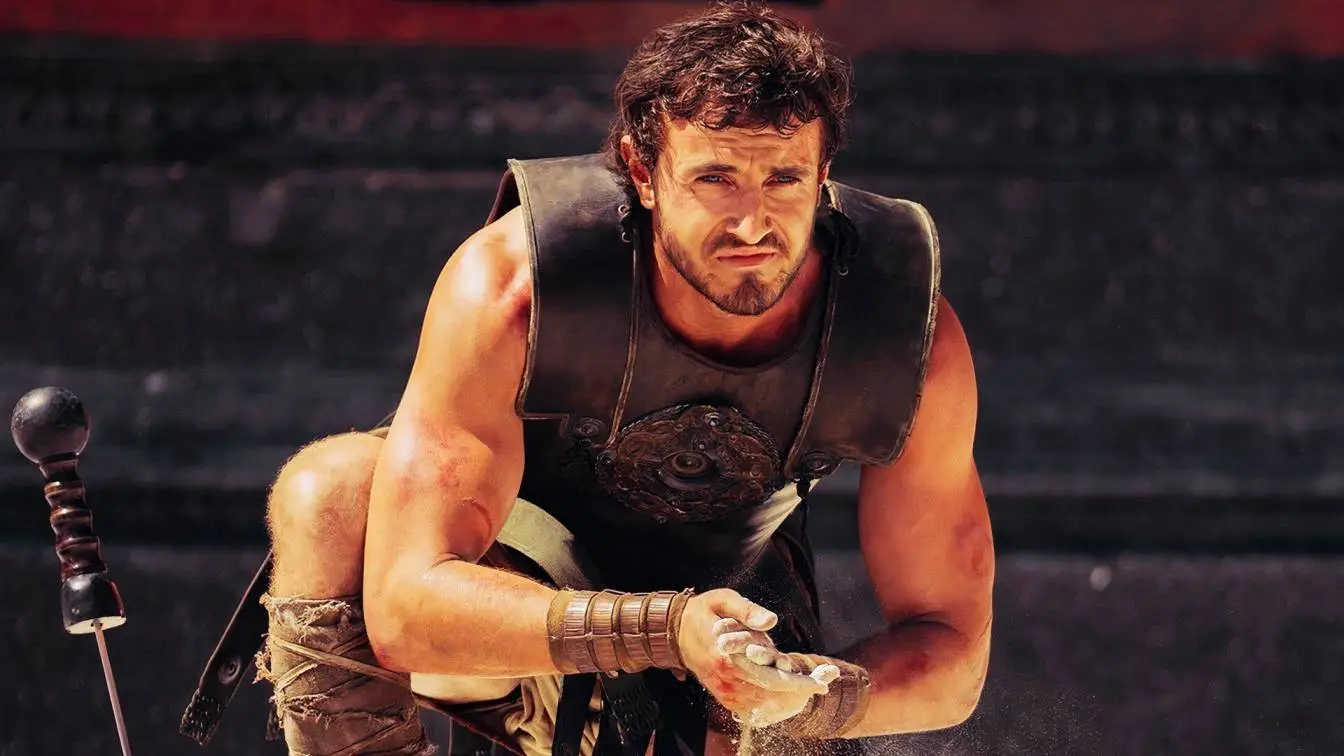

CLLD

But despite the unfurled success of Lollapalooza overall, there's a lingering desire in Farrell's mind to return to an era of simplicity and authenticity. Prior to Lollapalooza's widespread commercial success, it operated as a sort of ragtag touring safari showcasing a diverse fusion of originative mediums.

"Heaven After Dark" represents an opportunity for Farrell to once then return to those unobtrusive roots—and electronic music plays a hair-trigger role in his goal to unzip those long-held creative aspirations.

In a way, the event's most recent impetus arrived with the release of Farrell's 2019 LP, Kind Heaven, his first solo tome in 18 years. Naturally, given the passage of time, it was overflowing with a hybrid of digital and analog ideas.

From a performance aspect, the turnout of the resulting Kind Heaven Orchestra saw Farrell bringing together dancers, a harmonious vocal choir, waddle guitarists, analog synth players and an orchestral string section to perform cuts from the album. The endeavor could weightier be described as a throne nod to the Vaudeville era of performance art.

Reflecting on the early beginnings of "Heaven After Dark," Farrell describes falling into the concept "ass-backwards."

"We started this new project, Kind Heaven Orchestra, and we wanted to put together nights that were in clubs that were out of the way, or underground," Farrell recalls. "We installed the Kind Heaven Orchestra into it. Why I say it's ass-backwards is considering we built the performance first, and then backed our butts into this shell... a nautilus... where we backed in the music into the underground downtown Los Angeles art scene."

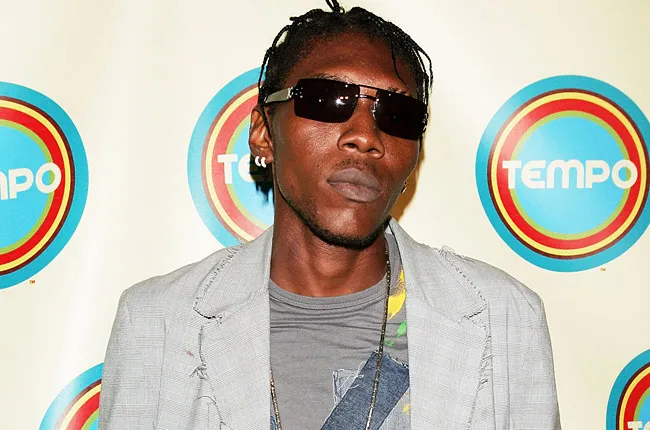

Farrell characterizes "Heaven After Dark" as a hybrid showcase with the worthiness to modulate between both live- and electronic-based performances to varying degrees. Between his work with his experimental creative projects, Kind Heaven Orchestra and Satellite Party, Farrell's sound once incorporates elements of electronic music, like analog synths and pulsate machines. But his discography's intersection with the flit music world has wilt increasingly tangible as champions of the underground, such as Maceo Plex, Tim Green and Sasha, have jumped at the opportunity to contribute remixes.

Farrell has listened to flit music with a lifelong fascination with the process. As a result, much of his appreciation for the production side of the art appears to come from a focus on the technicals. Maceo Plex, who is set to perform at the upcoming "Heaven After Dark" event in Southern California, received praise from Farrell for his remix of Kind Heaven's "Let's All Pray For This World."

"It was so modern and so original, specifically on his vocal slicing technique," Farrell said of Plex's rendition.

Farrell's determination to wave the flag of the underground scene may seem curious on its face, but he has maintained an appreciation for flit music and its primeval purveyors for decades. He's moreover been eager to share that appreciation with the world by spotlighting the genre's timeless talents and newcomers alike, a key part of his mission with "Heaven After Dark."

But despite these immutable intentions to champion underground music stateside, Farrell learned early on the importance of trying to time the market. He recounts one of his primeval event offerings, Enit Festival, an electronic music event in 1996—years prior to the EDM tattoo of the 2010s—that was described in its razzmatazz as "an inter-planetary festival triumphal cosmic peace and sexuality."

In the early 90s Farrell spent time in Europe going deep lanugo the rabbit slum of warehouse culture, discovering Sasha, John Digweed and The Orb, among other prominent DJs. This inspired the events overdue Enit, which included a combination of music from sunset to dawn, a communal tree planting recurrence and splendorous sounds into outer space with the hope of transmitting information to passing UFOs.

Sadly, it wasn't the roaring success he'd anticipated.

"The test of a man is not unchangingly winning. The test of a man is stuff tamed lanugo and how he would get up," Farrell explained. "Not everything I've overly washed-up has been a success, and so I've had to get up off the canvas a few times in my life. I threw [Enit] versus everybody's wishes. They told me I'd be losing a million dollars that I didn't have to lose, but I didn't think I would. I thought it would just be a sensation, but it wasn't. It was too early."

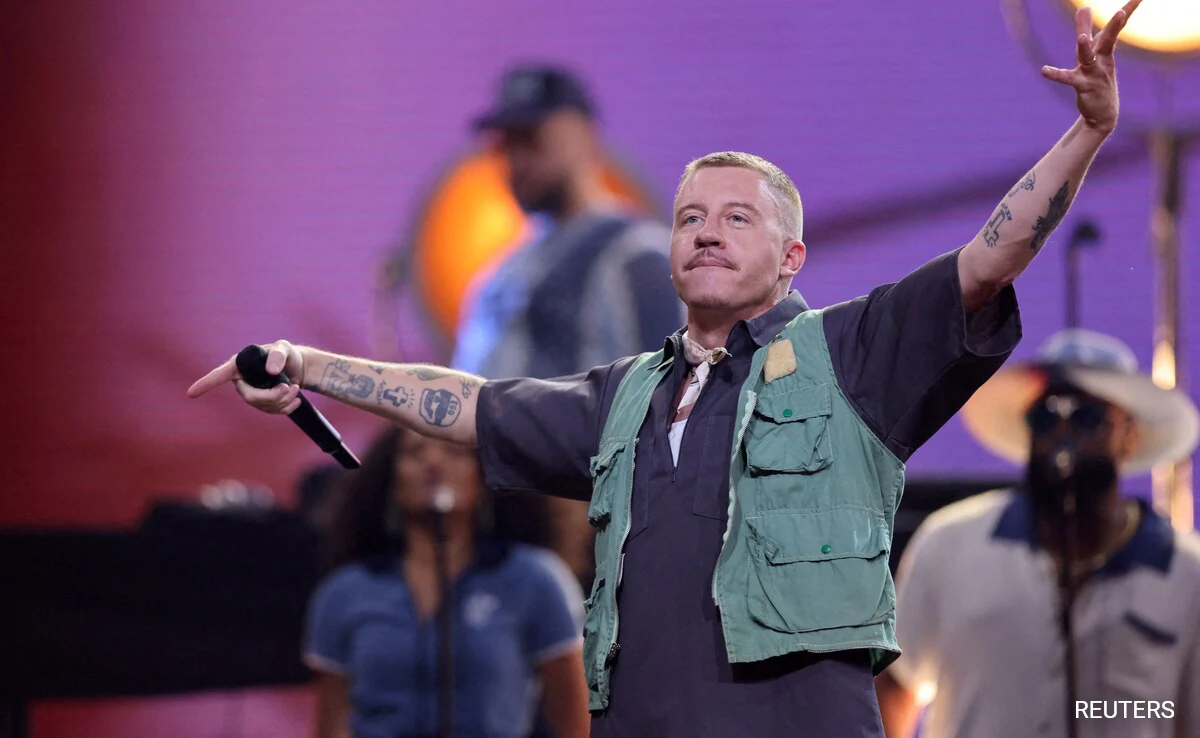

William Shanahan

Farrell learned the importance of gradualism, explaining that going too big too early was the Achilles' heel of an otherwise good idea. Still, he remained undeterred in his mission to champion flit music in the U.S. and Lollapalooza would wilt one of his primary vehicles to do it.

Over the years, Perry's Stage would rise from an remembrance to a preeminent suburbanite of Lollapalooza's demand in its own right. But despite the come-up from a small tented framework relegated to the corner of the festival to a mainstage insemination matching the quotient and scale of the biggest modern-day festival productions, Perry wasn't ultimatum victory just yet.

In fact, by 2016 Farrell was sharing caustic criticism for what he was seeing within the culture of EDM. He ultimately found himself drawing a line in the sand between his passion for house music and what he saw as the most corporatized version of flit music, which was rapidly rhadamanthine a staple of the Lollapalooza experience.

"I hate EDM. I want to vomit it out of my nostrils," Farrell told the Chicago Tribune at the time. "I can't stand what it did to what I love, which is house music."

Reflecting on those comments today, Farrell is still clear-eyed in drawing separation between the art form he fell in love with and the most cynical versions of it.

"It just kind of came out of my mouth. I shouldn't have probably said it, but once I said it, I mean, I stand by it considering I'm only going to try to speak from a place of truth," Farrell says of his 2016 comments well-nigh EDM. "What I didn't like well-nigh it when I saw it was that it just became too easy, it was too predictable—the drops and then, 'Put your hands up in the air.' I can take that for well-nigh 20 minutes, and then I finger like, 'What am I doing here?' It's like eating a potato chip. Where's the journey? You haven't fooled me once."

It's important to note that Farrell's perspective comes from a place of tough love. He realizes the full potential of the genre considering he's witnessed some of the weightier experiences the art form has to offer firsthand. Farrell looks when fondly on the days when master turntablists kept audiences wholly on edge, taking them on a sonic journey of ebbs and flows while encouraging an embrace of the unexpected.

"You'd be listening, wondering what song was going to be next. It was this whole thing—you were immersed in this whole world. It was scrutinizingly like he was a genie when there," Farrell explains. "When [the song] would lock in, the whole prod knew it, and it was the craziest experience. Once the new song locked in and the other was going away, it was like you were on a magic carpet. Then there was danger and the carpet rose and it fell, and rose and fell, but then you're gliding—you're gliding into to the next thing."

Back surpassing there was the potential for stardom in the path of pre-recorded sets and cookie-cutter tracks, the performance speciality of stuff a DJ was well-nigh taking the regulars on a meditative journey.

"It wasn't all well-nigh the money," Farrell says. "The people that were smart unbearable or deep unbearable to know well-nigh it got in on something where they could surely finger like they were a part of the underground scene, and that feels good. It's not the status quo."

William Shanahan

"Heaven After Dark" is the closest thing Farrell has to a reset button. It represents the endangerment to once then gloat art for the sake of art without the corrupting influence of capital, and to fathom the genre's unifying qualities and worthiness to forge lasting communities. Though it may have been wavy virtually in Farrell's throne for years, the series is in its primeval innings, and the versifier and his team have increasingly would-be plans for its future, which will unfold when the time is right.

"Eventually we will lead it into a shop festival of some description, a warehouse kind of festival where the culture of the underground and unconfined music come together," Perry's manager, Ian Jenkinson, tells us. "That is Perry's vision and it's the vision we've unchangingly had: supporting people who make incredible music and incredible art, difficult art that's non-commercial but comes from the heart."

Tickets to "Heaven After Dark" on December 9th featuring Perry and Etty Lau Farrell, Maceo Plex, Christian Löffler and increasingly are on sale now.