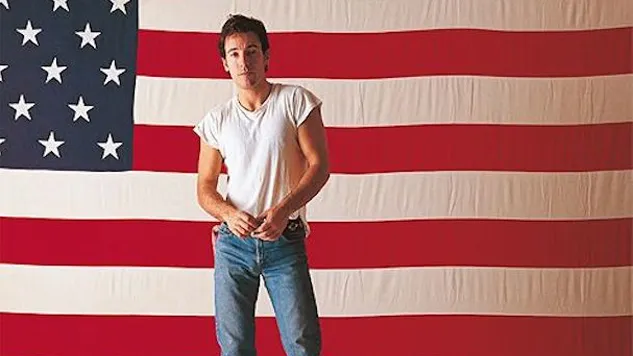

Bruce Springsteen was feeling nervous as the spring 1984 release of born in the usa movie neared, bringing with it one of the biggest commercial ascents in the history of popular music. It had nothing to do with "Dancing in the Dark," which he added at the last minute when his management persuaded him to compose one more guaranteed success song. It had nothing to do with the album's title tune, a thunderous hymn whose chorus might be mistaken for a catchphrase for jingoism from the Reagan era. Furthermore, it had nothing to do with the cover image, an Annie Leibovitz shot that could pass for a guy peeing on an American flag. It was a song named "No Surrender," and specifically the last line of the song:

As he sung these lyrics, something seemed wrong. Who could have such unbridled optimism? Springsteen attempted to rework the powerful arrangement into a gentle acoustic ballad; he revised the lyric and altered his delivery. The Born in the U.S.A. tour, which lasted 16 months and brought the E Street Band to the largest audiences they had ever played for, was one such attempt. It was only intermittently used in setlists toward the conclusion of the run. Years later, he remarked, "I was uncomfortable with the song." You don't always persevere and come out on top in life. You give in, lose, and drift into the murky places of existence.

How did it end up on the record, then? It wasn't because a scarcity of content. The majority of casual fans are aware that while Springsteen was assembling this full-band masterpiece, he recorded a completely different song in 1982, Nebraska, a solo acoustic that was meant to be a demo for the follow-up to The River in 1980. However, that wasn't the only source of it. Springsteen followed Nebraska's folky course with story-song leftovers like "Shut Out the Light" before settling on the twelve songs that would become his best-selling album. He also collaborated with the band on epics like "This Hard Land" and straight-ahead rockers like "Murder Incorporated." He composed a bizarre, post-apocalyptic song about the Klan and a silly song about getting his narrative made into a TV movie.

This was a decade into his music career, in his early 30s, and a time of deep reflection and soul-searching. Springsteen skipped a tour in support of Nebraska for the first time following the release of an album. Rather, he took a road trip across the nation with a friend for vacation.

In reaction, he went to treatment. He visited the gym as well. A great deal. In the book Bruce by Peter Ames Carlin, he observed, "I was a big fan of meaningless, repetitive behavior." "And what could be more pointless than picking up a heavy object and placing it back where you found it?" He was good at weightlifting, and slowly but surely the skinny, scruffy misfit from the Jersey beachfront began to resemble the main character in an action movie; someone who could actually play a hot auto mechanic in a music video and, you know, have his ass shot on the cover of an album.

Additionally, Springsteen's music-related culture was changing. Springsteen's new image helped him gain momentum in a medium that was all about images. In the meanwhile, cassettes had replaced vinyl, and now compact discs were taking their place. (Born in the usa movie was marketed at its debut as the first CD produced in the United States; the majority of earlier releases were imports from Japan.) Pop radio adapted to the new technology by favouring electronic dance music, which Springsteen believed to be an innovative invention. He penned one of the album's songs, "Cover Me," initially for Donna Summer, and you can detect her influence in his ferocious, percussion-heavy performance. He added, "I didn't like the covert racism of the anti-disco movement, and she could really sing."

Somewhat exaggerated is the '80s gloss of Born in the U.S.A. due to its monoculture appeal. It's a clean, well-produced tune with synth pads, big drums, and prominent vocals that epitomize popular rock production of the decade. However, when listening to it again, I'm impressed by how alive and tangible the music seems. In a matter of takes, the band recorded the majority of the songs live, with Springsteen shrieking off-mic, whooping, and shouting signals. And the writing is as bit as intelligent and poignant as any of his less polished work, fusing the tighter pop structures of The River with the complex tales of Nebraska.

The E Street Band's sound is what gives this a distinctively pop music-like vibe. Particularly potent synth work comes from Roy Bittan: in "I'm on Fire," a taught fuse doubles as a secondary bass line, while in "Dancing in the Dark," a heavy dampness contrasts with the train-track velocity. Drummer Max Weinberg frequently assumes the lead role, making decisions with snare beats that equal the intensity of Springsteen's protracted runner's high during the turnarounds in "Glory Days" and the title track. His command of the group is so tight that during the fadeout codas of songs like "Cover Me" and "Dancing in the Dark," their background tracks border on electronica. Dance producer Arthur Baker made intriguing club remixes of the sound at the time, which bands like the War on Drugs would later rework as a form of psychedelic music.

Springsteen's commercial makeover excited label executives, who reportedly got up from their chairs to dance during the playback sessions after the wilfully unmarketable Nebraska. (One stated he might have really peed his pants after hearing single after single, each better than the last and all mixed by Bob Clearmountain to sound like they were meant for radio.) It was also a benefit for Jon Landau, the former music critic turned manager, whose aspirational songs—some of which were truly about the life-saving power of rock music—gratified his long-standing conviction in the power of rock music. Springsteen himself was aware of the significance of this change as he had previously begun to analyze and critique his career. He would later remark, "I was fascinated by people who had become a voice for their moment." It was something I was interested in, but I'm not sure if I thought I had the ability for it or if I simply forced myself in that direction.

One guy showed little interest in the situation. It was Steven Van Zandt, the guitarist for E Street Band, a man who has unique insight to the inner workings of an artist's mind. Growing up as like-minded outsiders in New Jersey, the two became friends during band fights and spent many evenings in each other's houses, avoiding their controlling dads and spreading the word about the music they cherished. Van Zandt is frequently recognized for having encouraged his friend to loosen up a bit when they started their careers together.

a producer's assistant on Van Zandt, an American-born singer, infuses these songs with the same feeling of optimism. "Darlington County" has the happiest moment. Springsteen begins to giggle as Van Zandt honks his way through the vocal harmonies, "He don't work and he don't get paid." "Boy, does that sound ugly," he thinks, but it's wonderful. The same is true of the mandolin section of "Glory Days," which Van Zandt spontaneously recorded into a voice mike in order to prevent editing it out without deleting the entire take.

These instances corresponded with a fresh strain between the two, which makes sense for an album that hides its nervousness under a glossy exterior. While finishing his own record, Voice of America, under the pseudonym Little Steven, Van Zandt's raw sound and protest-oriented ethos seemed incongruous with Springsteen's newest commercial endeavors. Van Zandt admitted to feeling a little underappreciated and broached the subject of marketing their records together on a combined tour. I love to think about how this concept might be received. Recognizing a turning point and having become accustomed to his friend's unwavering independence, Van Zandt left the group.

Read Also: Zack Snyder Confirms Rebel Moon Director’s Cut Titles

Although Springsteen maintained his position, he wasn't as sure of himself as he appeared. He invited guests into his home to go through the many cassettes and put together a tracklist while he went for runs or patiently waited at the kitchen table. With an excess of material, he expanded his creative process outside the inner circle. Chuck Plotkin, his engineer, even presented an acetate copy of the record he imagined. In a five-page letter, Landau defended his preferred order. In the end, Springsteen submitted his finished record after heeding some of their counsel and ignoring a lot of it.

Van Zandt wasn't a big fan of "Dancing in the Dark," so he played it for him. He had an idea of rock'n'roll nirvana where everyone is young and attractive and always strutting, and the lyrics, with their self-conscious and sensitive tone, were a distaste. Additionally, avoid starting the production with him. Nevertheless, the absence of his favourite song, "No Surrender," remained his biggest worry. Springsteen added the song back in at the last minute, starting it at the beginning of Side B.

For a well-known perfectionist such as Springsteen, this procedure may seem random, but it kind of was. He still feels uneasy when he talks about being born in the usa movie. What he is most pleased of are the bookending tracks, "My Hometown" and the title track, which are the two overtly political pieces that made the cut. "I've always had mixed feelings about the songs on the rest of the album," he writes.

That's how "No Surrender" deserves its standing; the hope is earned and ultimately condemned to be fleeting. He sings against the beat, "You say you're tired and you just want to close your eyes and follow your dreams down." But which way down? The direction of the compass's steady arrow would be down in the vast, open landscape of this record. Also is mentioned in the first line of the song, "Born down in a dead man's town," and also represents the couple's future plans in the last line, "My Hometown," as they prepare to transfer their family and "maybe head south." It's a syllable that gets stretched into a comic, rockabilly hiccup in the chorus of "I'm Goin' Down," and it's where all the signposts of security—work, marriage, community—send the narrator of "Downbound Train." Down becomes home base for many of the characters in these songs; it's the direction you're told not to go in while you're at the top, the inevitable fall that follows any high.

"Bobby Jean" is the next song on the list after the fleeting ecstasy of "No Surrender," and although Springsteen has never stated that Van Zandt was the inspiration for it, fans have long assumed that it is. "Bobby Jean," like all of his work on friendship, plays with the vocabulary of love songs; the gender is purposefully left open-ended. Just before the last stanza comes the important line, which is a straightforward yet powerful selection of words: "Now there aren’t nobody, nowhere, no how/Gonne ever understand me the way you did." comprehend me, not love me, not know me.

There would be additional sayings of farewell. In the following five years, Springsteen would divorce Julianne Phillips, his first wife; fire the E Street Band following the 1987 tour for Tunnel of Love, which was primarily a solo project; move from New Jersey to Los Angeles to raise a family with bandmate Patti Scialfa; and finally try to shed his celebrity identity by withdrawing from the public eye and admitting that he felt "'Bruced' out" following the attention and mania that born in the usa movie brought into his life.